Hunger And Insecurity: What The Recurring Recession Means For Nigerians

By Anita Eboigbe

A lot of Nigerians did not need the government to announce a recession. They felt the pangs long before the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) made a statement on November 22.

They already knew it had come and made some peace with reality when the prices of staple foods and services increased dramatically.

Still, the announcement gave their suffering a name – one that they had presumed was behind them.

A lot of Nigerians might not understand the economic jargon used to explain the recession but they can feel hunger and growing insecurity.

They know when they can no longer afford food and when they fear for their own lives – events that recessions have been known to cause and maintain.

In 2016, Nigeria went through a full year recession which the NBS described as the country’s worst at the time, since 1987.

This record has been broken by the decline experienced in 2020 which is currently touted as the worst yet.

In 1987, according to World Bank data, Nigeria had a full-year decline in the gross domestic product (GDP) at 10.8 per cent.

The country recorded shakeups in 1991 and 1995, recording a full-year economic decline of 0.6 and 0.3 per cent respectively.

According to the NBS GDP report released on Tuesday, Nigeria recorded a contraction of 1.51 per cent in 2016.

“In the fourth quarter of 2016, the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted by -1.30 per cent (year-on-year) in real terms, from 18,533.75 billion naira in Q4 2015 to 18,292.95 billion naira in Q4 2016,” NBS said.

“This decline was less severe than the decline recorded in the previous quarter, of -2.24 per cent, but was nevertheless lower than the growth rate recorded in the final quarter of 2015, of 2.11 per cent.

“Quarter on quarter, real GDP increased by 4.09 per cent, which partly reflects seasonal factors as well as a rise in the general price level. For the full year 2016, therefore GDP contracted by -1.51 per cent, indicating real GDP of 67,984.20 billion naira for the year.”

Speaking on the 2016 recession, CBN Governor, Godwin Emefiele said, “the average monthly inflows of foreign exchange into the CBN fell from over 3.4 billion dollars in June 2014 to as low as 500 million dollars in October 2016.

“The decline in foreign exchange earnings was further complicated by the foreign capital flow reversals from emerging markets due to the interest rate hike in the USA.

“The impact of this decline on our economy was evident in the rise in the value of the US Dollar relative to the Naira; and a rise in the Consumer Price Index due to the increase in the cost of imported inputs, food items, petroleum price, transportation costs, as well as goods and services,” he added.

By 2017 onwards, the public believed the economy began to return to normal and people started getting used to the economic ‘normal’.

However, there was nothing normal about the situation. The economy was trying to recover and citizens were trying to work their way around it.

Then, COVID-19 hit, oil prices fell and the ball dropped again. This time, quite further than anticipated.

Nigeria relies on crude sales for 90 per cent of foreign exchange earnings and the country normally accounts for an average output of two million barrels per day.

However, the effects of the pandemic and low oil prices have cut production to approximately 1.4 million barrels.

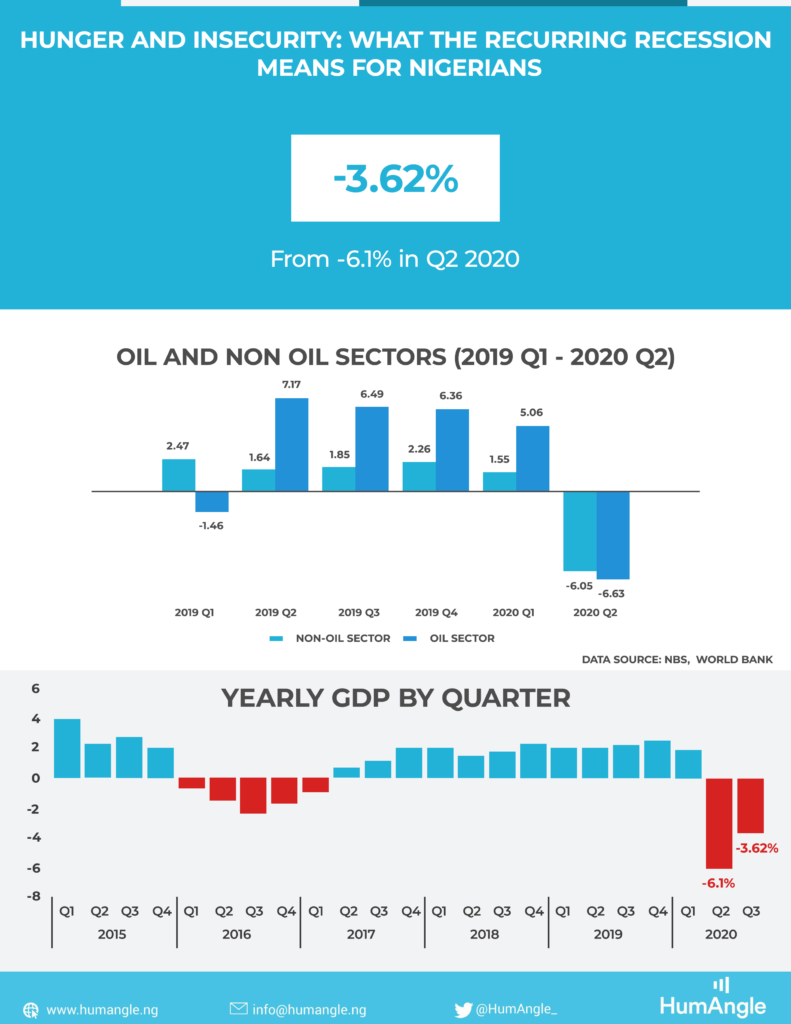

“Q3 2020 Real GDP contracted for the second consecutive quarter by -3.62 per cent,” Yemi Kale, the statistician general, said on Twitter on Saturday.

“Cumulative GDP for the first nine months of 2020, therefore, stood at -2.48 per cent,” he added.

The oil sector contracted by 13.89 per cent in the third quarter against growth of 6.49 per cent in the same period a year earlier, while non-oil sectors shrank by 2.51 per cent in the three months to September.

“The performance of the economy in Q3 2020 reflected residual effects of the restrictions to movement and economic activity implemented across the country in early Q2 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic,” NBS said in a report published on Saturday.

“As these restrictions were lifted, businesses reopened and international travel and trading activities resumed, some economic activities have returned to positive growth,” it said.

This is the second recession under President Muhamadu Buhari’s democratic reign — and his fourth as head of state.

Experts say that the 1983 recession is, however, not directly attributed to him, as he took power on the last day of the year.

People Are Hungry

An onion, in most Nigerian cities, now costs N100. A few weeks ago, the same amount could buy five onions.

Like onions, prices of other staple food have greatly increased and the result is widespread hunger.

Staple foods like rice, yam, beans and eggs have become almost unreachable alongside certain essential services.

Jeff Okoroafor, a Social commentator, said, “In the economy, we are back in recession for the second time in five years. Hunger and starvation and unemployment continues to rise.”

Like him, several people have been vocal on social media about the hunger that is spreading across the country. The phenomenon did not come out of the blues.

For a while, there had been calls from several quarters, including HumAngle nudging the government to a looming food security crisis, especially with the lockdown, insecurity and climate change issues.

In March, HumAngle reported that Nigeria’s food security is under siege as climate change continues to disrupt farming activities for smallholder farmers.

The report highlighted that “70 per cent of rural dwellers are subsistence farmers, who produce about 90 per cent of Nigeria’s food. According to the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the disruption by climate change is affecting food production across the country.

“These farmers actively contribute to economic growth. In 2018, agriculture contributed 21.2 per cent to Nigeria’s Gross Domestic Products (GDP) in 2018.

“Farmers, however, decry lack of support in combating climate change-induced threats and shocks, which include, high rising temperatures, erratic rainfall patterns, prolonged drought, and flash floods.

“All these have led to massive land degradation, poor agricultural input and output, insecurity and unpredictable market prices, which undermine agricultural productivity and threaten the livelihood of millions of rural households,” the paper reported.

In April, HumAngle spoke with agricultural experts who expressed fear that food security might be threatened in Nigeria due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

They also pointed out that the agricultural infrastructure had been weakened over the years and is not sustainable for domestic consumption or exports.

In May, the paper posed the question ‘Should Nigeria be worried about looming food insecurity?’ and went on to warn, again, about the hunger currently experienced.

The report reads, “Before the outbreak of COVID-19, Nigeria already occupied the infamous position of the world poverty capital and its northern region was ranked among the top 10 places with the worst food crises.

“By putting the bulk of economic activities on hold, not sparing the agricultural sector, the ongoing pandemic threatens to make the situation worse.

“According to the World Food Programme (WFP), previous estimates indicate that over 21 million people across West Africa will have difficulty feeding themselves between June and August if not assisted.”

In August, residents of Oke Ogun axis of Oyo State warned of an impending food crisis if efforts were not made to check incessant kidnappings and other crimes on farmers and other citizens in the area.

The people spoke in interviews with HumAngle following numerous unreported cases of such activities.

All these warnings and more offered time for the Nigerian government to plan out ample mitigating measures, especially with the clear knowledge that the economy was going to experience a recession.

The NBS report, which eventually announced the recession was not by chance.

Read Also:

Experts, including government officials, had hinted at the possibility although not much was put in place to cushion the effects, in terms of insecurity and hunger.

Recession Foretold

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) had predicted a 5.4 per cent drop in Nigeria’s GDP in 2020.

Also, the government had previously said it expected the economy to contract by as much as 8.9 per cent this year in a worst-case scenario without stimulus.

In August, analysts warned that COVID-19 lockdowns and the drop in demand for oil were hurting the Nigerian economy, which second quarter (Q2) of 2020 GDP figures confirmed on August 24.

Oil production fell to 1.67 million barrels a day from 1.81 million barrels in the previous quarter, according to Bloomberg figures, the lowest since the third quarter in 2016 when the economy last experienced a recession.

The World Bank forecast the Nigerian economy will contract by 3.2 per cent in 2020, assuming the spread of COVID-19 is contained by the third quarter. The IMF also forecast a contraction of 4.3 per cent.

Before the pandemic and its attendant disruption, the Nigerian economy was expected to grow by 2.1 per cent in 2020.

The pandemic occasioned by border closure has seen the country record sustained inflation for more than two years, with the October figure of 14.25 per cent, the highest in the last 30 months.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) in September, cut interest rates to 11.5 per cent to help boost borrowing and support the economy. It was the second reduction in months.

A World Bank report showed that the human cost of COVID-19 could be high. Beyond the loss of life, the COVID-19 shock alone is projected to push about five million more Nigerians into poverty in 2020.

“While before the pandemic, the number of poor Nigerians was expected to increase by about two million largely due to population growth, the number would now increase by seven million – with a poverty rate projected to rise from 40.1 per cent in 2019 to 42.5 per cent in 2020,” the report said.

The report noted that the pandemic is likely to disproportionately affect the poorest and most vulnerable, in particular women.

It added that over 40 per cent of Nigerians employed in non-farm enterprises reported a loss of income in April-May 2020.

Also, the fall in remittances is likely to affect household consumption because half of Nigerians live on remittance-receiving households, of which about a third are poor.

“The unprecedented crisis requires an equally unprecedented policy response from the entire Nigerian public sector, in collaboration with the private sector, to save lives, protect livelihoods, and lay the foundations for a strong economic recovery,” said Marco Hernandez, World Bank Lead Economist for Nigeria and co-author of the report.

In October, President Muhammadu Buhari said that the country was heading for another recession, the second in four years.

The President, who made the remarks while presenting the 2021 budget proposal to the National Assembly, spoke against the backdrop of a significant increase in deficit beyond the provisions of the Fiscal Responsibility Act, following revenue pressures faced by the government.

He noted, however, that the Federal Government has put in place plans to ensure rapid recovery in 2021.

He said, “The 2021 Budget was prepared amid a challenging global and domestic environment due to the persistent headwinds from the coronavirus pandemic.

“The resulting global economic recession, low oil prices and heightened global economic uncertainty have had important implications for our economy.

“The Nigerian economy is currently facing serious challenges, with the macroeconomic environment being significantly disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic,” he added.

The deficit, inclusive of government-owned enterprises and project-tied loans, is projected at N5.2 trillion, which represents 3.64 per cent of estimated Gross Domestic Product, (GDP) 0.64 percentage point above the 3.0 per cent threshold set by the Fiscal Responsibility Act, 2007.

Explaining this position, Buhari, however, said, “We still face the existential challenge of coronavirus pandemic and its aftermath; I believe that this provides a justification to exceed the threshold as provided for by the law.”

Giving further details on the deficit, the President said, “The deficit will be financed mainly by new borrowings totalling 4.28 trillion naira, 205.15 billion naira from Privatization Proceeds and 709.69 billion naira in drawdowns on multilateral and bilateral loans secured for specific projects and programmes.”

Insecurity Is Worsening

In March, HumAngle detailed the effects of the dwindling economy, especially from the falling oil revenues, on Nigeria’s security efforts.

At the time, oil price stood at 25 dollars per barrel and a week’s market plunge, Nigeria lost over 335.7 million dollars.

At 2.18 million barrels per day on a cost of 57 dollars per barrel, as captured in the 2020 budget, Nigeria stood a chance to earn about 124.26 million dollars daily. As of March 18, that calculation was like a pipe dream.

The difference between the projected earnings (124.26 million dollars per day) and the actual earnings (76.3 million dollars daily) was 47.96 million dollars.

The report noted that Nigeria has been through this dance before where the economic recession was the best catalyst for the insurgency.

In 2014, oil prices, which previously averaged 115 dollars, went from 73 dollars to 65 dollars, the beginning of a downward hill ride to the recession that shook the country in 2016.

Between mid-2014 and early 2016, the global economy faced one of the largest oil price declines in modern history.

The 70 per cent price drop during that period was one of the three biggest declines since World War II and the longest lasting since the supply-driven collapse of 1986.

In 2015/2016, as Nigeria arched closer to the recession, Boko Haram intensified its attacks and began to cut the country’s legs from under, forcing then President Goodluck Jonathan to apply drastic measures.

In early 2014, the frequency and scale of Boko Haram attacks, mainly targeting civilians, increased significantly. In February, the group killed at least 59 people, when its fighters opened fire at a secondary school in Yobe State. In March, at least 75 people were killed in blasts that occured in Maiduguri, Borno State, attributed to Boko Haram.

In April, Boko Haram gunmen abducted 276 schoolgirls from their dormitory in northeastern Borno State, merely hours after more than 70 people were killed in a bomb attack near Abuja.

Recently, in the last couple of weeks and days, the number of kidnapping victims have jumped. Citizens are growing weary of road travels because of fear of bandits, terrorists, armed robbers and kidnappers.

In the past month, 620 people have been killed in 34 states across Nigeria and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) as a result of political violence and other cases of insecurity.

This was according to an analysis of data from the Nigeria Security Tracker (NST) between October 20 and November 20, 2020.

Out of this number, 293 were civilians, 64 were security operatives, two were political actors, and one, 20-year-old Pelumi Onifade, was a journalist. Other casualties included 128 Boko Haram members, 124 armed persons, eight armed robbers, two sectarian actors, and a kidnapper.

The highest death tolls were recorded in Borno (163), Katsina (72), Lagos (68), and Kaduna (64). They were followed by Zamfara (34), Edo (26), Cross River (18), Delta (15), Plateau (14), Yobe (12), among others.

Only two states were without fatal incidents: Bauchi and Gombe. This is not the time for the government to do little or do nothing.

The recession has proven to be the best breeding ground for starvation and alarming insecurity. Nigerians need to be looked after.

Credit: HUmAngle