Analysis: Kill One Terrorist, Create A Thousand More: What Fuels Terrorism In The Sahel?

by Ahmad Salkida

With the killing of Abdelmalek Droukdel (also known as Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud), head of Al Qaeda in the Maghreb by French forces in Mali, attention is drawn to the elements fueling extremism and jihadist terrorist activism.

On a day that thousands staged a massive protest against the French propped government of President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita in Mali, West Africa, the French military stationed in that country announced that their forces had killed Abdelmalek Droukdel, leader of Al Qaeda in the Maghreb.

Taken together, that announcement took the fire from the thunder in the significance of the mass protest in Bamako, led by the President of the High Islamic Council of Mali, Mahmoud Dicko, the protesters rose in their thousands on Friday afternoon, at first, taking over Independence Square and demanding the resignation and exiling of Keita.

A few hours in the Independence Square, the protesters marched towards the official residence of the president in Sebenikoro. The riot police stepped in and dispersed the protesters but letting heavy tension hang over the city.

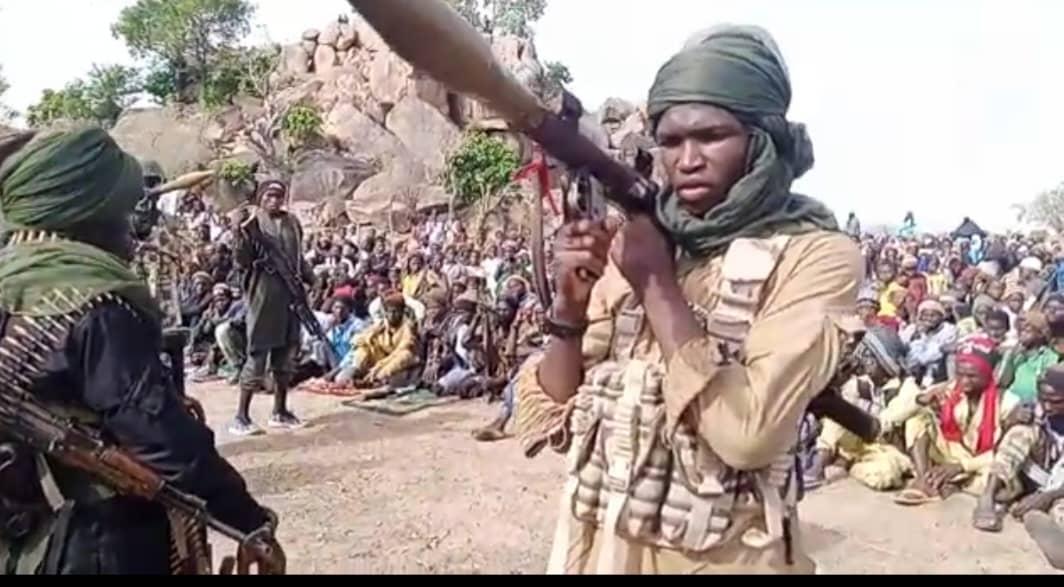

With the deepening corruption in governments across African states, compounded by unmet expectations among youths, the attraction for fulfilment in extremist jihadist doctrines peddled by social psychos such as Abdelmalek Droukdel in the Maghreb and Abubakar Shekau in the Lake Chad regions continues on the upward trajectory.

In the decades preceding the terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre in the United States of America, on September 11, 2001, and several years afterwards, radical young Muslims made destinations such as Afghanistan and other locations in the Middle East the ultimate initiation ground for a lifelong mission of jihadi.

To kill a Westerner, say an American, an Israeli or be killed by a Westerner was most desired honour for these jihadi troops. It was considered far more dignifying to kill or be killed by a Westerner than to kill or be killed by local security forces in sub-Saharan Africa.

Enthusiastic youths washed up with delusionary religious utopia drive themselves in utter desperation to get enlisted in the ranks of jihadists flocking the battle terrains of the Middle East.

Those who could not make it to the battlegrounds in the Middle East and Afghanistan ended up on the desert fringes of Mauritania, Algeria and Libya. These areas became training grounds and transit zones for Jihadi migration.

The trend is, however, changing with increasing jihadi wars springing up across the sub-Saharan Sahel region. Many of these fighters have returned and taken up leadership positions across the Lake Chad and the Sahel regions.

According to Abdulbasit Kassim, a PhD candidate in Religion at Rice University and a Visiting Doctoral Fellow at Northwestern University’s Institute of Islamic Thought in Africa, “Bad governance and the French military presence have always been a factor for recruitment into jihadist groups.”

In the case of Mali where Droukdel was killed, Kassim said, “the population is averse to the French presence, the Malian government as well as the jihadists. The jihadi groups do not enjoy public sympathy and other mainstream clerics like Mahmoud Dicko, have more grip over the youthful population. Dicko’s influence on the youths is evident in the protest he led against Ibrahim Keita,” Kassim argued.

“No need to travel to the Middle-East to spill the blood of infidels like the Americans, Jews and French, they are right here in our backyard,” said one Boko Haram fighter.

Across Africa, there is growing resentment against corrupt regimes not given to meeting the expectations of the population. This situation is worsened by economic hardship. The Jihadi exponents always on standby to exploit the situation.

Across Africa, there is growing resentment against corrupt regimes not given to meeting the expectations of the population. This situation is worsened by economic hardship. The Jihadi exponents always on standby to exploit the situation.

Read Also:

Mali’s situation is typical and tending towards the failed state status. Keita was accused by the protesters in Bamako of rigging the last elections, and also not doing enough to secure the release of Soumalia Cisse, who was abducted alongside some members of his campaign team who were later released by a Jihadi group.

As the protest raged, the French Defence Minister, Florence Parly, wrote on Twitter: “On June 3, the French armed forces, with the support of their partners, neutralised the emir of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Abdelmalek Droukdel and several of his close associates, in the course of an operation in northern Mali.”

The head of the United States Africa Command, Col. Christopher Karns, said the U.S. played a key role in the French-led operations by providing intelligence information and surveillance aircraft to help with the mission but failed to comment on whether the raid resulted in the death of Droukdel.

According to Rukmini Callimachi and Eric Schmitt in a detailed report in the New York Times, Droukdel’s group, “now known as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, expanded its area of operation beyond Algeria.”

“Mr Droukdel’s katibas, or battalions, were operating in Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Tunisia and Libya,” said the report.

The group financed its operations by building a network of kidnapping-for-ransom rings across those countries for several years. It is believed that the group might have grossed about 91 million dollars in kidnapping-for-ransom deals from 2008.

Analysts believe that internal rifts between Droukdel and Moktar Belmoktar, an influential terrorist in the region who had headed one of Droukdel’s most active battalions, created a rival. Moktar, which reportedly denounced Droukdel, created a parallel terrorist group, seeking direct contact with Al Qaeda.

This is similar to the drama that has played out in the Lake Chad region where highly placed commanders from Boko Haram broke away from Shekau to create an affiliate of Islamic State in what became known as Islamic State West Africa Province, (ISWAP).

This is similar to the drama that has played out in the Lake Chad region where highly placed commanders from Boko Haram broke away from Shekau to create an affiliate of Islamic State in what became known as Islamic State West Africa Province, (ISWAP).

The rivalry extends beyond Al-Qaeda linked groups in the region, IS affiliates in the region see the killing of an influential leader of Al-Qaeda in the region as an advancement of their influence. They consider Al-Qaeda as much a threat to their ambitions in the region as the state forces battling them in the countries in the Sahel.

Already, Islamic State sympathizers, as HumAngle gathered, are blaming the killings of Droukdel on Al-Qaeda’s non-Takfiri stand that accommodates some level of inter-dependence between Jihadists and host communities or other non-Jihadi networks.

“We must cut off ties completely with people outside our fold,” said an IS sympathiser. Another one said information about Al-Qaeda activities travel fast, IS must learn from this and never give the enemy the chance to infiltrate its ranks.”

A diplomatic source in Abuja, who follows developments in the Sahel closely, said, the coming together of Jihadi groups in the Sahel, likely inspired a recent statement by JNIM and Droukdel simultaneously, calling on Jihadists to “avoid harming ordinary Muslims and not to attack civilians” contrasted sharply with the views of IS.

The presence of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) led by Abu Walid al-Sahrawi, collaborating with the West African affiliate (ISWAP), roughened JNIM’s path in the region. Sources have reported the killings of hundreds as a result of clashes between the two groups.

A recent video seen by HumAngle, shows ISWAP executing two ANSARU members, a group mainly in Northwest Nigeria with direct links to JNIM. In the video, ISWAP accused the ANSARU members of working with Al-Qaeda to infiltrate and undermine the group.

These groups know each other far more than what the security officials know about them, “because they once fought side by side,” said a security official in Abuja. “And when these Jihadists are apprehended, they mostly reveal what they know about a rival group than what obtains within their group.”

As the local authorities and western forces strengthen co-operations to respond to growing threats in the region, criticisms trail the G5 and Multi-National Joint Task Force in Lake Chad and other competing European and US military bases as ineffective in curbing the spate of recruitments and attacks that are growing all over the region.

HumAngle gathered that the underlying reason for the rivalries amongst Jihadi groups in the Sahel may be racism. A top ex-Boko Haram fighter who fled in-fighting in Lake Chad, early this year, said, he was met with derogatory remarks by light-skinned Jihadists and could not take it like the rest of the fighters, “so I fled with my family to Sudan.”

Kassim agrees that racism is an issue in the Sahel, with an example from the book of Bruce Hall, “A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600-1960” that chronicles the racial tension in the region, which predated the advent of the jihadist campaign in the region.

But jihadist leaders seem to have overcome racial differences by working with various racial groups to carry out coordinated attacks against local and international forces in the region, Kassim argued.

If at all there is this problem then it might be “more prevalent among the foot soldiers than the upper echelon,” he added.